I wrote on Instagram that What’s For Dinner? (1978) was ‘like Ivy Compton-Burnett’s characters leapt forward a century and took to drinking cooking sherry’ and I’m half-tempted to leave my post simply at that. But perhaps I’d better say more.

James Schuyler first crossed my radar as a chance purchase in Hay-on-Wye – I bought, read, and loved his novel Alfred and Guinevere, which is the most realistic portrayal of the way children speak that I’ve ever read. What’s For Dinner? is also chiefly concerned with how people speak – and you hope that it’s not realistic, though it probably is.

The novel opens with a dinner party. Norris and Lottie Taylor have reached the stage of marriage where they ignore and rile each other with equanimity, neither of them discontented and neither of them particularly happy at where life has left them. Coming to visit is the Delehantey family – Bryan and Maureen, their twin teenage sons Nick and Michael, and Bryan’s mother Biddy. They are a ramble of chaos by comparison, proud of their old-fashioned values – which mostly take the form of Bruce being dominant and forever quashing any sign of life from his son, Maureen being houseproud and judgemental, and Biddy sassing them all. (It’s hard not to love Biddy, for all her complaining and martyr complex – she’s one of the few characters unafraid to be exactly herself.)

From the opening pages, we know this is going to be an unsettling but fun journey. The set-up might be quintessentially American Dream of well-off neighbours being neighbourly over apple pie, but everything is always slightly at odds with everything else. The hosting couple bicker while not really listening to each other. The visiting family don’t really want to be there. Nobody hates anybody else, but everybody is mutely exasperated by everyone else.

One of the reason this novel made me think of Ivy Compton-Burnett is how heavily dialogue is used. Here is a section, which also shows Schuyler’s brilliant way of weaving together clichés, antagonisms, banalities, and the disconnect when interlocutors all want to talk about something different:

“Competitive sports,” Bryan said, “make a man of a boy. They prepare him for later life, for the give and take and the hurley-burley.”

“You might say, they sort the men from the boys,” Norris said.

“Do you mean that?” Bryan asked, “or is that one of your sarcasms?”

“It could be both,” Norris said. “I wasn’t much of an athlete, so I have to stick up for the underdog.”

“You ought to take up golf.”

“As the saying goes, thanks but no thanks.”

“Norris always looks trim,” Mag said. “Do you go in for any particular exercise?”

“Just a little gardening. A very little gardening.”

“I thought you had a yardman,” Maureen said, “who came in and did that.”

“We do. But Lottie doesn’t trust him around the roses. No more do I, for the matter of that.”

“Roses,” Biddy said, “the queen of flowers.” She shook out the crocheted maroon throw, so all could see it. “Isn’t this just the color of an American Beauty?” It wasn’t, but if anyone knew it, no one said it.

If a lot of the character work is done through conversation, then it’s bits like those final words that really sold me on What’s For Dinner? – ‘It wasn’t, but if anyone knew it, no one side it’. I love it when an author undercuts his cast, gently ridiculing their pretensions and falsities.

The dinner scene goes on for so long that I wondered if it would be a one-scene novel. But no. We get a clue where What’s For Dinner? might go when Lottie takes a break from socialising to go to the kitchen – and down some wine.

When the second part of the novel begins, Lottie is living in a residential home for alcoholics, trying to be cured. We’re introduced to a wide array of patients and their visiting spouses and families, variously bitter, over-enthusiastic, withdrawn, and brash. The same dialogue-heavy approach continues, but now the characters are even more unhinged and unlikely to speak with anything resembling logic.

Group was in session, and Dr Kearney looked bored. “All right, Bertha,” he said, “you’ve made yourself the center of attention long enough. We’ve all heard your stories of marijuana, music and LSD. You’ve convinced us that you were a real swinger, and you swung yourself right in here.”

“You never talk about your problems, I’ve noticed,” Lottie said, “the things behind your actions. That might be more interesting and helpful. To all of us, not just yourself.”

“My only problem,” Bertha said, “is that I have a family. They’re nice, but they bug me.”

“Bug you?” Mrs. Brice said.

“They let me do anything I want, but all the time I can tell they secretly disapprove. They don’t know what to make of me , but I know what to make of them. Spineless. Nice, but spineless.”

“We haven’t heard much from you, Mrs Judson,” Dr Kearney said.

“I never did talk much,” Mrs. Judson said.

“That’s true,” Sam Judson said. “Ethel was never much of a talker. She shows her feelings in other ways.”

“In other ways?” Norris said. “I’d be interested to hear an example.”

I wondered if Schuyler would be able to sustain the brilliance of his tone with this wider cast and more serious topic, but I needn’t have worried. If there was something particularly excellent about the brittle tension of a dinner party, then there is something equally exhilarating about seeing Schuyler rope more people into the madness. We lose the subtext of a dinner table representing so much more – but he handles both small-scale and crowd dazzlingly. In fact, the only dud note in the novel comes in the scenes of teenagers – either the twin boys together or when we see them with a wider gang. The dialogue doesn’t ring at all true, and let’s just say he falls into a common trap with twins that I complained about the other day. It’s curious, considering how good he can be at conversation between younger children.

Schuyler is apparently best known as a poet. From reading his prose, I really couldn’t guess what his poetry would be like. It seems he only wrote three novels, the third being A Nest of Ninnies, co-authored with fellow-poet John Ashbery. I’m quite sad to have nearly come to the end of his novelistic output, because he is such a lively and piercing writer of prose – but perhaps I should give the poetry a go.

Look, yes, I’m cheating again – The Home (1971) isn’t a novella, since it’s 230 pages, but I had a bit more time to read today, and I thought I’d spend it here. And I’m so glad I did – The Home is brilliant (and, indeed, rather better IMO than the other Mortimer I read earlier in May, My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof).

Look, yes, I’m cheating again – The Home (1971) isn’t a novella, since it’s 230 pages, but I had a bit more time to read today, and I thought I’d spend it here. And I’m so glad I did – The Home is brilliant (and, indeed, rather better IMO than the other Mortimer I read earlier in May, My Friend Says It’s Bullet-Proof). his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending.

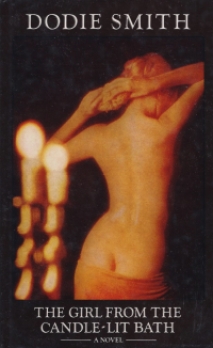

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending. This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.

This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be. Oops, I keep cheating on this novella challenge – though today’s cheating was accidental, since I was about 30 pages into Journey Through A Small Planet (1972) by Emanuel Litvinoff when I realised it was an autobiography. Simply from seeing it on the shelf, I had assumed it was a sci-fi novella – though that in itself would have been a surprise, being worlds away from

Oops, I keep cheating on this novella challenge – though today’s cheating was accidental, since I was about 30 pages into Journey Through A Small Planet (1972) by Emanuel Litvinoff when I realised it was an autobiography. Simply from seeing it on the shelf, I had assumed it was a sci-fi novella – though that in itself would have been a surprise, being worlds away from

Blaming was Elizabeth Taylor’s final novel, written while she knew she was dying – and death and mourning are very much at the heart of the book. It opens with Amy and Nick on a cruise. It is to celebrate Nick’s recovery after months of illness, and the first chapter or so is what you might expect of a Taylor novel set at sea – acute observations, gentle interactions, characters reflecting on their own lives as they go about the minutiae of each day.

Blaming was Elizabeth Taylor’s final novel, written while she knew she was dying – and death and mourning are very much at the heart of the book. It opens with Amy and Nick on a cruise. It is to celebrate Nick’s recovery after months of illness, and the first chapter or so is what you might expect of a Taylor novel set at sea – acute observations, gentle interactions, characters reflecting on their own lives as they go about the minutiae of each day.