I loved Andrew Haigh’s film All of Us Strangers and think it’s criminal that Andrew Scott and Jamie Bell haven’t won every award under the sun (and Paul Mescal and Claire Foy can have some too). It sent me off to read the novel on which it was loosely based – Strangers (1987) by Taichi Yamada, translated from Japanese by Wayne Lammers. Interestingly, the original Japanese title translates as ‘Summer of the Strange People’, so it’s had a few metamorphoses.

There’s nothing more irritating that somebody comparing a novel to an adaptation if you haven’t seen it, so I’ll just say that Haigh made plenty of changes to his screenplay for All of Us Strangers – though probably not as many as you might imagine by his slightly disingenuous remarks that he ‘doesn’t remember’ what happens in the original novel.

I listened to the audiobook, so won’t be able to quote from the novel – but here’s the premise. Hideo Harada lives alone in a big apartment block which is in fact mostly offices, and hardly anybody else lives in the building. He is recovering from divorcing from his wife, not mourning the relationship so much (the divorce was his decision) as he mourns the life it gave him. Hideo is a middle-aged TV scriptwriter who only really seems to have one close friend – a TV producer with whom he has worked, and who reveals he is planning to ask Hideo’s ex-wife to marry him. It is the death knell to their friendship and (the producer insists) to their professional relationship. The only other person in his life is his adult son, whom he doesn’t see very often.

Despite these sadnesses, Hideo is not a very emotional man. He wishes some circumstances were different, but he doesn’t seem to rail against them particularly. He is a man used to tragedy: his parents died in an accident when he was a teenager. And when connection is offered to him, he doesn’t take it up. A beautiful young woman, Kei, is the only other person in the apartment block one evening. She comes to his flat, hoping she can join him for a drink. He turns her away.

Not long later, Hideo bumps into Kei by the lifts. One thing leads to another, and they start a friendship that quickly becomes a sexual relationship. So quickly that it’s hard to tell exactly what is propelling it, besides our repeated assurances that Kei is beautiful.

The far more interesting relationship is happening simultaneously. On a whim, Hideo goes back to the neighbourhood where he grew up. He goes to a show, and Yamada has some fun at the expense of a mediocre comedian in a sort of variety show. From the back, Hideo hears a man call out, and thinks he recognises the voice – but he can’t see the man. After the show finishes, though, this man beckons Hideo to go with him. He doesn’t seem at all surprised to see Hideo, nor does he think Hideo will object to going. And Hideo follows, dumbstruck.

I’m going to say why, though do skip if you’d like to go into Strangers entirely without spoilers.

The man looks and sounds exactly like… Hideo’s father. Despite the fact that Hideo’s father died more than 30 years ago. This man hasn’t aged since that date – he is, in fact, rather younger than Hideo himself. Hideo follows him back to his humble home… and finds the doppelganger of his mother there too. He hasn’t time travelled, because all the modern conveniences are present. So what’s going on? They both speak to him affectionately and without reserve. I was struck by how some of the nuances of Strangers were lost by being in translation: my understanding (from context clues in the novel, and from reading Polly Barton’s Fifty Sounds about the Japanese language) is that there are many different grammatical impacts that depend on the register used. For instance, a parent speaking to a child would use different verb endings (maybe?) to a friend speaking to a friend, or a stranger speaking to a stranger. I imagine Yamada makes most of this function of Japanese, in the maelstrom of confusion and trying to establish precisely what is going on and what relationships are at stake.

Strangers is a short novel, so the emotional impact of this encounter is dealt with efficiently. There is plenty of plot and we aren’t given much time to linger in these emotions – which gives the book a feeling of spareness, reluctant to let the reader or the characters get bogged down in the full implications. I think it works, though it could have worked equally well if a longer work had been dedicated entirely to this surreal relationship.

Instead, Strangers hovers on the edge of horror. I didn’t find it particularly scary, which I was nervous about, but it certainly incorporates ideas of fear rather than simply nostalgia or love. Chilling is perhaps the word, though in a way that is interesting rather than challenging. The fear doesn’t come from the encounter with his parents, or parent-like people – rather, it is his own deepening illness. People keep remarking how unwell he looks – how gaunt, like he has the sudden weight-loss of aggressive cancer. But when he looks in the mirror, he seems perfectly fine. What is going on, and is it connected to his visits to his ‘home’?

I thought Strangers was unusual and very good. It’s trying to do things in a genre that I don’t fully understand, and I’ve read so few Japanese novels that I don’t know how much of an outlier it is. Plot-wise it has a lot of similarities with the All of Us Strangers film. Tonally, it is often worlds apart. Both are experiences I can firmly recommend.

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending.

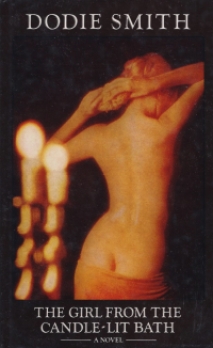

his 1987 book was translated from Norwegian by Don Bartlett in 2013, which is when I think I got it as a review copy. Well, here I am, almost a decade later I’ve read all 118 pages of it. There seems to be some disagreement about whether this is a novella or a series of short stories – it’s kind of both, in the way that Tove Jansson’s The Summer Book is. Arvid Jansen is an eight-year-old boy in the 1960s, living with his family on the outskirts of Oslo, with a scathing older sister, a worrying mother, and a father who never stops speaking about ‘before the war’. There is also a grandfather, who dies in one of the first chapters/stories – a brilliant portrait of a young child’s mingled grief and indifference, scared of things changing but not really in mourning, and trying with inadequate words to convey all he is experiencing but not really comprehending. This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.

This was Dodie Smith’s last novel, written when she was in her 80s, and it is quite a departure from her earlier work. While I Capture the Castle might feature the heroine in a bath when she first encounters the hero, nobody would describe Smith’s most famous work as a thriller. And that is what The Girl from the Candle-Lit Bath is at least trying to be.