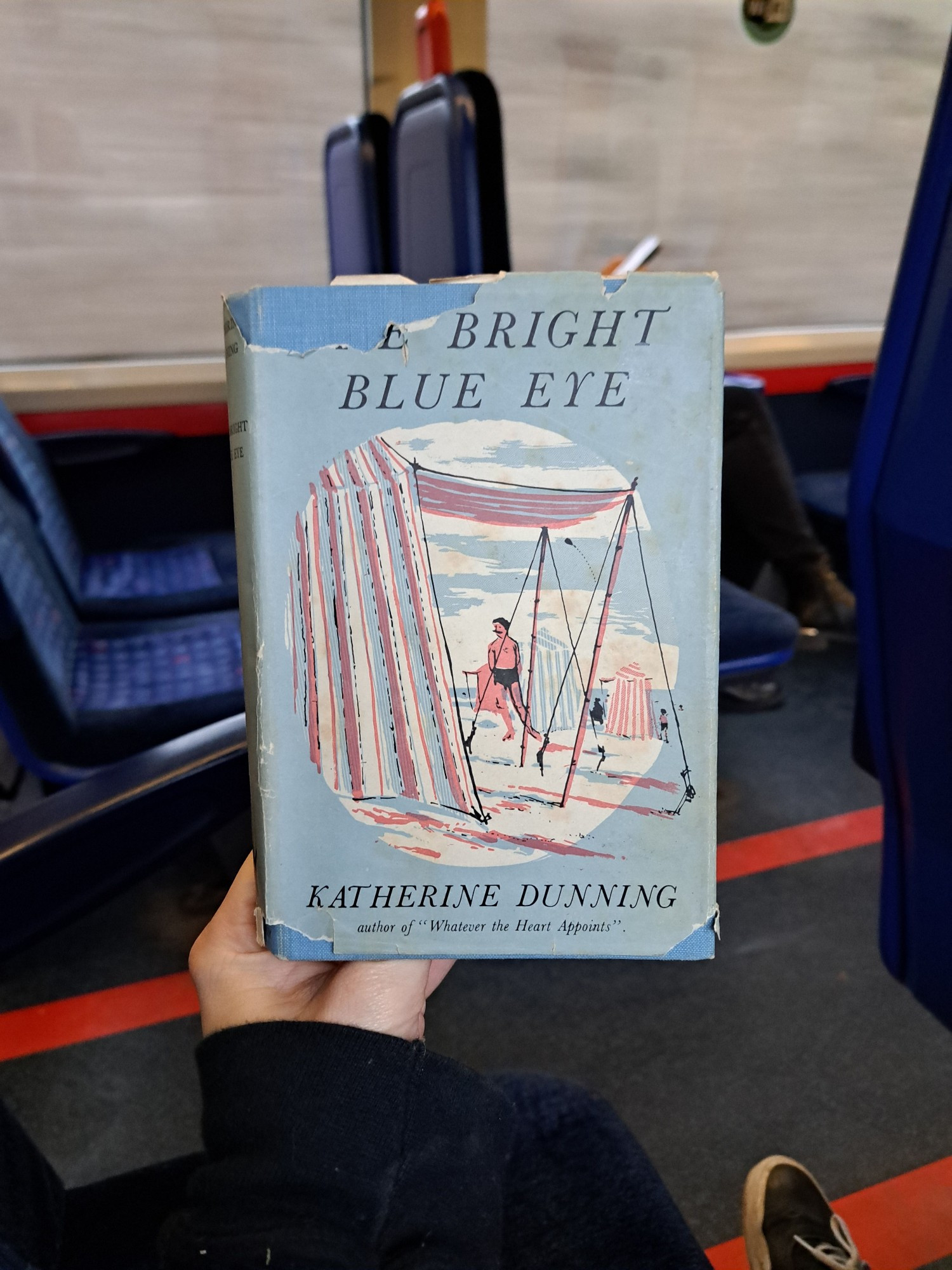

The Spring Begins by Katherine Dunning was my favourite read of last year, and has been reprinted in the British Library Women Writers series (hurrah!) so naturally that set me off to see what else Dunning had written. At the time, the only one I could find online was The Bright Blue Eye – though now Dunning’s great-niece has sent me her other three books, which is extraordinarily kind of her.

Dunning wrote a handful of books in the 1930s and then a couple in the 1950s – this is the last of her output, and very different in tone from The Spring Begins. Where that one is lyrical, with deep insight into people’s emotional cores and their hopes, The Bright Blue Eye is much lighter and much wittier. At the heart of it is an eccentric family – with the most ‘normal’ member being the narrator, Kate, about whom we learn relatively little. She is really a focal point for a bizarre group.

The most eccentric, and the most memorable, is Father – a wonderful creation, whose kind-heartedness is matched only by his thoughtless enthusiasm for inventing. Worried about getting everyone into the home? He makes collapsible three-tier bunk beds that can be wheeled around the house at will – though, sadly, are not collapsible enough to get through the door. His brother is innocently tending to the garden, and Father leaps at the opportunity to create an automated digger – which will clearly destroy everything in his wake. The ‘bright blue eye’ of the title is his eye, brightening at the idea of invention. His other passion is architecture, specifically cathedrals, and he delights in telling everyone the many flaws of the most celebrated cathedrals. Here he is, talking to his son Crispin’s fiancée:

Poor Beryl’s face looked tired, but she was still determined to see the best side of us. We must be nice, we really must be nice people, since we were Crispin’s family. Let her hold fast to that thought. She forced a look of animation back into her eyes, and waited for Father’s next words. Up till now she had not realised that this country, and certainly not Europe, boasted so many cathedrals, and all of them wrong. If she had thought of our national monuments and buildings at all, she had thought of them with respect and pride. But not any longer! Those happy inconsequent days were gone for ever. She knew better now, but acquiring this knowledge had been tiring, a top-heavy culmination to a difficult day.

I found Mother a less dominant character, despite the blurb on my edition claiming ‘it is their mother, whose beauty and calm ride tranquilly over tempers and discomforts, who is the centre of the picture’. It would certainly be a more chaotic dynamic without her, though I’m not sure how effective she is – particularly when she is a little blind to the foibles of her younger children.

There’s the youngest – bold, confident Hugh, who speaks in a seemingly affected childish patois, all missing verbs and articles. But he is overshadowed by Miranda. She seems, frankly, like a sociopath. Brilliantly clever, she wins all manner of prizes at school – but is the terror of teachers and classmates alike. She takes great pleasure in exaggerated prophecies of doom. For instance, when someone bangs their head, she declares “Skull broke, I think. Terrible hard bang. House still trembling.” Though a terrifying character in the abstract, she is not terrifying here. It is her own brand of precocious non-conformity, and nobody takes her particularly seriously.

There are a bunch of other characters I’ve not talked about, from angelic Fenella to longsuffering Cousin Clare, and each gets their moment in the sun in the novel. If I had to compare to another writer, The Bright Blue Eye reminded me most of Betty Macdonald. It is less hyperbolic, but still a witty eye cast at a bizarre family, loving in their own way. It is also similarly episodic. While things do progress, there isn’t really a through-line to the plot, and I did find that the novel didn’t have much forward momentum. I think one of the hardest things to identify is why a book does or doesn’t have this momentum. The Spring Begins did; The Bright Blue Eye didn’t – and yet neither have a stereotypically ‘plotty’ plot.

The Spring Begins is definitely the better book, but I still enjoyed The Bright Blue Eye whenever I picked up. The writing is so enjoyable, often so funny, and there are great set pieces – like a terrible shift in a cafe, or befriending lorry drivers when two lorries break down on their rickety driveway, or the chaos on a French beach that lends the novel its cover. Reading this novel has also got me curious about Dunning as an author: she clearly has a great deal of range, and I wonder what her ‘voice’ is like, distilled down. Luckily I now have her other books, so will be able to put together a picture!