I’ve recently read two books by Arnold Bennett about being an author, both published in 1903 – one fiction and one non-fiction. He’s one of those authors who was ubiquitous during his lifetime, and now only seems to be remembered fleetingly for a couple examples of his prolific output. Neither The Truth About An Author nor A Great Man are in that number, as far as I’m aware.

I’ve recently read two books by Arnold Bennett about being an author, both published in 1903 – one fiction and one non-fiction. He’s one of those authors who was ubiquitous during his lifetime, and now only seems to be remembered fleetingly for a couple examples of his prolific output. Neither The Truth About An Author nor A Great Man are in that number, as far as I’m aware.

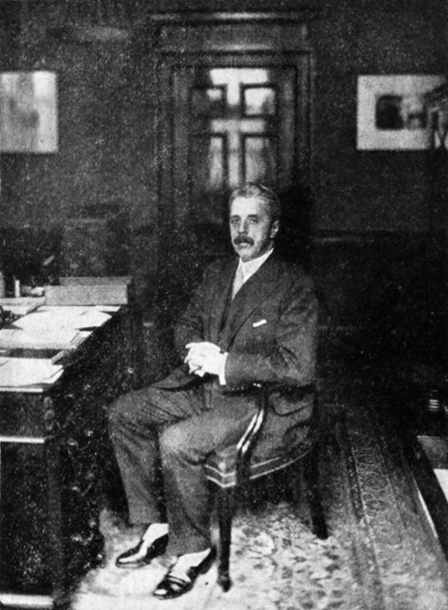

The Truth About An Author (1903) is the non-fiction one, and was written astonishingly early in his career. At this point, he’d only published a handful of novels, though had also made something of a name for himself as a journalist and reviewer. The edition I have is a reprint from 1914, for which Bennett was written a rather bizarre new preface – very defensive about how it was received the first time around:

The book divided my friends into two camps. A few were extraordinarily enthusiastic and delighted. But the majority were shocked. Some – and among these the most intimate and beloved – were so shocked that they could not bear to speak to me about the book, and to this day have never mentioned it to me. Frankly, I was startled. I suppose the book was too true. […] The reviews varied from the flaccid indifferent to the ferocious. No other book of mine ever had such a bad press, or anything like such a bad press. Why respectable and dignified organs should have been embittered by the publication of a work whose veracity cannot be impugned, I have never been able to understand.

Never trust somebody who thinks the only negative thing about their book can be an exaggerated good trait! ‘Too true’! It is hard to see, though, why The Truth About An Author should cause any great shock. It is a bit silly and self-congratulatory, but a lot of books are that. It essentially tells the story of Bennett’s rise from a jobbing journalist to a prodigious book reviewer, then to someone who tried writing stories and discovered he was good at it. He has a successful serial, tries writing plays, etc.

The most memorable section is where he talks about being a reviewer – and boasts that he can read and review a book within an hour. Or, rather, that he doesn’t read the books. ‘In the case of nine books out of ten,’ (he says) ‘to read them through would be not a work of supererogation – it would be a sinful waste of time on the part of a professional reviewer.’

It’s odd to put a preface on a book that essentially prepares the reader to dislike it, and if he hadn’t I’d probably have enjoyed it more. But there is no doubt that Bennett comes across a little silly and self-satisfied – and would sound still sillier if he didn’t happen to be extremely successful.

In the same year, he had similar things on his mind for fiction. A Great Man: A Frolic follows Henry Shakspeare Knight from his childhood to his successful life as a novelist and playwright. The opening scenes deal with his infancy, and his cousin Tom was a substantially more interesting character – who fabricates stories about his baby cousin escaping from his crib. A few years later, we see Henry’s issues with dyspepsia and Tom seeking to escape a future of drudgery in work. It’s an interesting family dynamic.

It feels a little like Bennett was making up the plot as he went along, as we soon ditch all the other family – but not before an attentive aunt writes down the story that Henry makes up when on his sickbed with scarlet fever. He titles it Love in Babylon and everyone agrees it is wonderful. Everyone, that is, except the editors to whom he sends it. The story is repeatedly rejected, not least because it is only 20,000 words long.

Eventually, though, it is taken as the inaugural title of a new line of silk-bound square books – and becomes an enormous success. Knight’s name is made, and he starts a (chaste) love affair with the agent’s secretary. He follows it up with A Question of Cubits, about a very tall man who falls in love – and some of my favourite stuff in the novel was Bennett writing about how the title took off in the popular consciousness, used equally in advertising and slang.

Knight is a success with the masses, but the intellectuals – including Cousin Tom, who reappears later in the book – dismiss and mock him. The novel reminded me a bit of Elizabeth Taylor’s Angel but with claws retracted. He is certainly not the monster she is. Just a bit pompous and silly… he could easily have written The Truth About An Author.

I enjoyed reading A Great Man – or, in fact, listening to the free Librivox recording of it. Woolf’s dismissal of him makes us forget what a talented writer he was, certainly on the level of the sentence even if his structures and plots can be a bit suspect. This novel doesn’t have any big point to make or a rug to pull from under anyone’s feet – it’s just a good, linear book about becoming a successful author.

I didn’t intend to read these in tandem, but they are fascinating that way – as two sides of the same coin.